How leaf monitoring from space changed one life in Bohemia

Jan is the most common name in the Czech Republic. It is no wonder then that Jan is the name of one of the farmers we recently contacted. He lives in a small village of around 400 people with his family, dog, two cats and several other animals. He’s been working in agriculture for his whole life. First at the state-run cooperative, but later on family fields, he received back from the state after the revolution in 1989.

He’s managing seven fields around nearby villages, growing mostly wheat, corn, and rapeseed. For most of his life, the crop yield was excellent, but in the last few years, there were too many things going on in parallel, and it was harder than ever to define priorities of fieldwork. And more importantly, Jan was afraid that his harvest was poorer than his peers’, and he couldn’t figure out why.

One day someone rang his door, it was a young lady with long brown hair and a big smile on her face. Jan was surprised; he had never seen her before, so he simply asked her “How can I help you?” She stepped further and started explaining, “My name is Veronika, and I’m currently discussing with farmers about their life and work. I’ve checked some satellite data before coming here, and I’ve seen that the crops in your field aren’t doing very well.” “Excuse me, satellite data? Are you spying on me?” wondered Jan.

It is common for farmers to be skeptical of someone looking at their field from a satellite. So this was no challenge to Veronika and she explained the benefits of satellite crop monitoring for farming. Jan, like many farmers, was aware of satellite technologies for autonomous machinery, but satellite crop monitoring was something new for him. As a fan of technology, he grew quickly excited finding new ways to use it and even needed to be calmed down a little..

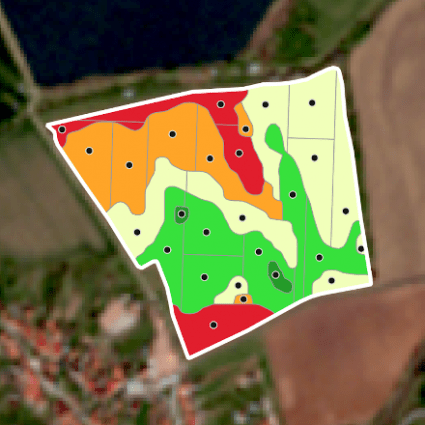

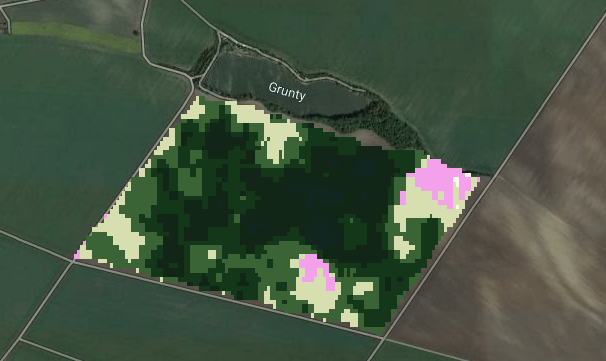

One of his favorites was the Leaf Area Index (LAI) that he could use to estimate if there is or isn’t a sufficiency of nitrogen in the field. LAI estimates canopy density as the leaf area (m2) per ground area (m2). This type of information is very beneficial because it is a reliable parameter for plant growth. So Jan can use it to compare exactly how much vegetation is currently on all his fields.

When LAI shows there are low values still during the growing season for crops that should gradually have more leaves, this may mean that there is a limitation in photosynthesis and plant growth, which can lead to a reduced yield. For Jan, this is a helpful tool helping him to optimise the timing and dosage of fertiliser.

To be honest, not many farmers are so quick to understand what satellite crop monitoring could bring to them. That is why we asked him to try to explain the concept of LAI to other farmers. He told them this: “Imagine you’re growing corn and the entire corn plant would be as tall as a house and the corn cob the size of a person. If you were to stand on a platform above the field and look down, you would see one corn leaf which overshadows an entire square meter of the ground. In that case, the LAI value would be ‘one’. If there were two leaves above each other blocking the view of the ground, the LAI value would be ‘two’.” Quite fitting, don’t you think?

On the other hand, there are also some pitfalls. Satellite-based leaf monitoring has its limits, as the LAI index stops responding to the reality approximately around value 5. More leaves won’t make any change in the monitoring.

It was a very pleasant visit for Veronika, as she chatted to Jan over coffee and homemade cake. But it was the same for Jan, who found out more about a tool he didn’t even know existed. It will be the first year he will test satellite monitoring as part of his farming. However, he already feels the joy of trying a new technology that can help him achieve higher yields and make better decisions.

There are several ways to enable farmers to use LAI within your app. DynaCrop is one of them. If you are interested in tentative discussion, please book a meeting with us at: